Long before jets and helicopters took over the skies, one man in France dreamed of a flying machine that could fly on its own. That man was Henri Giffard. On September 24, 1852, he flew in the first powered, steerable airship.

This wasn’t fantasy. This was a steam-powered, hydrogen-lifted reality.

The Visionary Behind the Machine

Henri Giffard was more than just an inventor. He was a dreamer with a fierce understanding of steam engineering. When he designed his dirigible, he wasn’t trying to break speed records. He simply wanted to prove that man could control flight, not just rise into the sky, but steer through it as well.

He succeeded.

Hidden Home Expenses That Have Drained Wallets for Centuries

What Made Giffard’s Airship Unique?

Before Giffard, balloon flights were essentially rides on the wind. Once aloft, pilots had no say in where they’d go or when they’d land. Giffard changed that.

His airship featured:

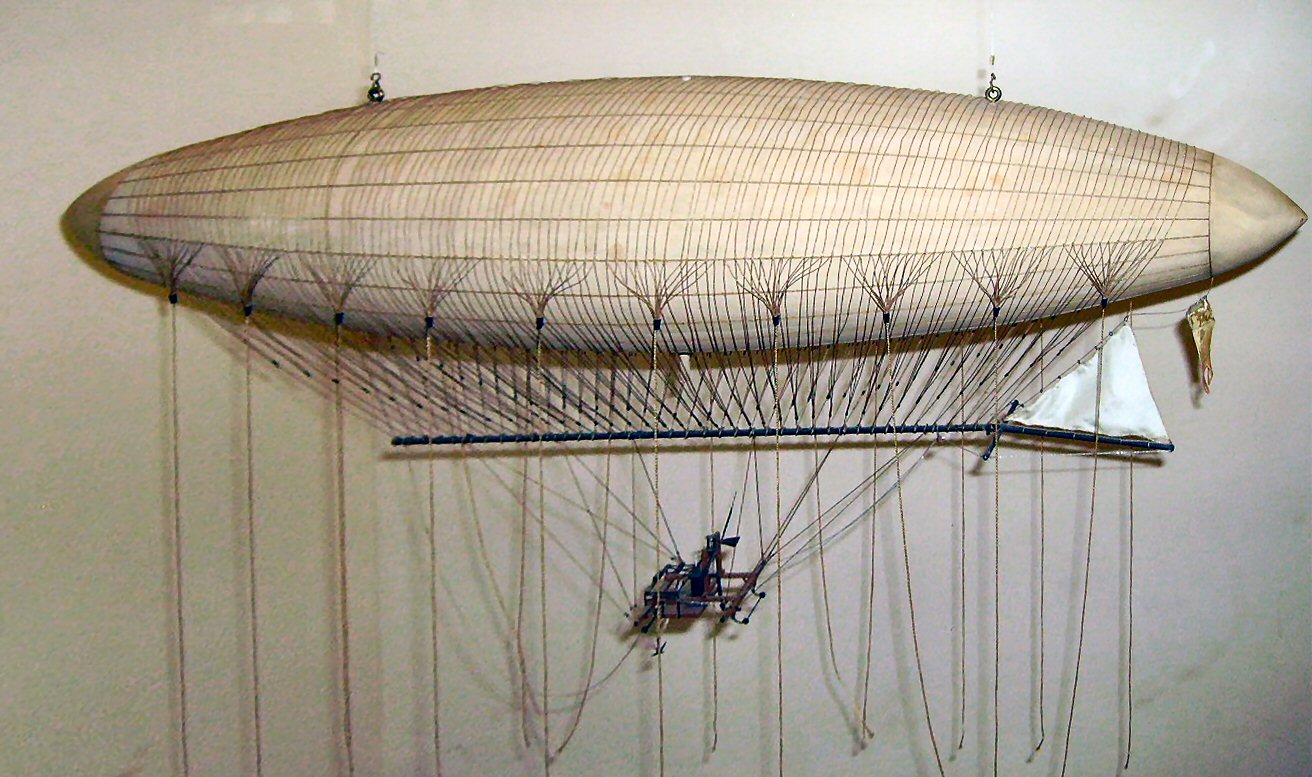

- A 44-meter-long hydrogen-filled envelope, tapered at both ends for better aerodynamics.

- A triangular rudder for steering is basic, but effective.

- A steam engine mounted on a platform beneath the balloon. It produced three horsepower, just enough to move the airship at around 9 kilometers per hour.

To manage the risk of fire (a genuine concern with hot engines and flammable hydrogen), Giffard:

- Redirected the engine’s exhaust down a long pipe, away from the balloon.

- Wrapped the boiler’s stoke hole in wire gauze to prevent sparks.

It was a delicate dance between fire and flight.

Lessons From History: Home Expenses That Never Pay Off

The Flight That Made History

On the morning of September 24, 1852, Giffard launched from the hippodrome at Place de l’Étoile in Paris. His destination: Élancourt, roughly 27 kilometers away.

The journey took about three hours.

And here’s what made it historic:

- He steered. He changed direction mid-flight.

- He proved control was possible.

It wasn’t only about getting to Élancourt. It was also about flying with purpose. That had never been done before.

A One-Way Ticket

Giffard’s engine wasn’t powerful enough to fight the wind on the return trip, so the flight was one-way. But it was enough to send a message to the world:

Controlled, powered flight wasn’t just possible; it had arrived.