On a seemingly ordinary morning at Camp Funston, Kansas, on March 11, 1918, a sudden and deadly turn of events occurred. Soldiers, who had been going about their daily routines, were suddenly struck with fever, chills, and sore throats, and were rushed to the infirmary. What appeared to be a routine flu outbreak would soon escalate into a global catastrophe, claiming the lives of tens of millions and forever altering the landscape of public health.

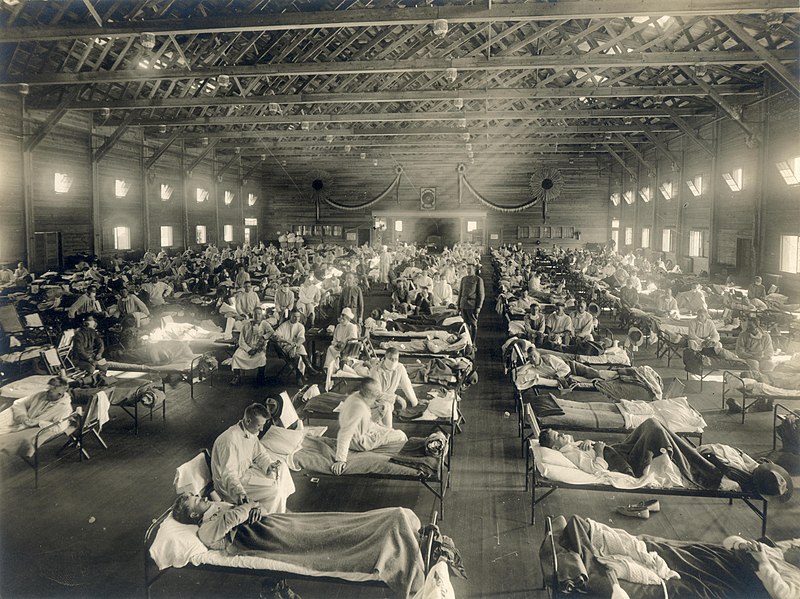

The first reported cases of what would later be known as the “Spanish Influenza” emerged at Camp Funston, a military base teeming with over 56,000 troops. By nightfall, more than 100 soldiers were stricken, and within weeks, over 1,000 men were hospitalized. The virus, spreading through the densely populated barracks at an alarming rate, was soon out of control. Despite its misleading name, the Spanish Flu did not originate in Spain. Many experts now believe its roots can be traced back to rural Kansas, possibly Haskell County. In January 1918, a local doctor noticed an unusual flu outbreak, striking healthy young adults with deadly pneumonia. Many of these men later reported for duty at Camp Funston, unknowingly carrying the virus.

Soldiers from Funston deployed across the country and overseas. By April 1918, military camps and cities across America saw outbreaks. The virus traveled with U.S. troops to Europe, where World War I trenches became a perfect breeding ground.

Spain became erroneously linked to the flu due to the open reporting of Spanish newspapers, which were not under wartime censorship. Other nations, like the U.S., Britain, and Germany, concealed their flu outbreaks to prevent a decline in morale during the war. The first wave of the flu in spring 1918 was relatively mild. However, by fall 1918, a more lethal second wave emerged. This wave was particularly deadly, often claiming lives within 24 to 48 hours, as the virus caused lungs to fill with fluid, suffocating its victims. The most terrifying aspect was that young, healthy adults—those in their 20s and 30s—were the hardest hit, a shocking anomaly for influenza.

By the pandemic’s end in 1919, estimates placed the death toll between 50 to 100 million people—more than the casualties of World War I. It remains the deadliest pandemic in modern history.