For centuries, scholars had studied the mysterious drawings of ancient Egypt, trying to decipher their meanings. These markings, known as hieroglyphs, were found throughout the region—on buildings, monuments, and tombs—yet there was no known way to decipher the information they recorded. Hieroglyphs represented a lost language; the knowledge to read or write them had long been forgotten. However, on July 3, 1799, a significant discovery changed everything when French soldiers uncovered the Rosetta Stone. This find provided the key to understanding the ancient language.

In late 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt with an army of French soldiers, aiming not only to control the region but also to study its ancient and rich culture. The soldiers were stationed near the town of Rosetta, and while they were busy repairing a broken fort, they made a significant discovery. A soldier named Pierre-François Bouchard noticed intricate inscriptions on a stone and recognized the potential importance of understanding the long-studied hieroglyphs of Egypt. This recognition of Bouchard and the discovery of the stone itself profoundly changed the understanding of ancient Egypt and alleviated centuries of frustrated study.

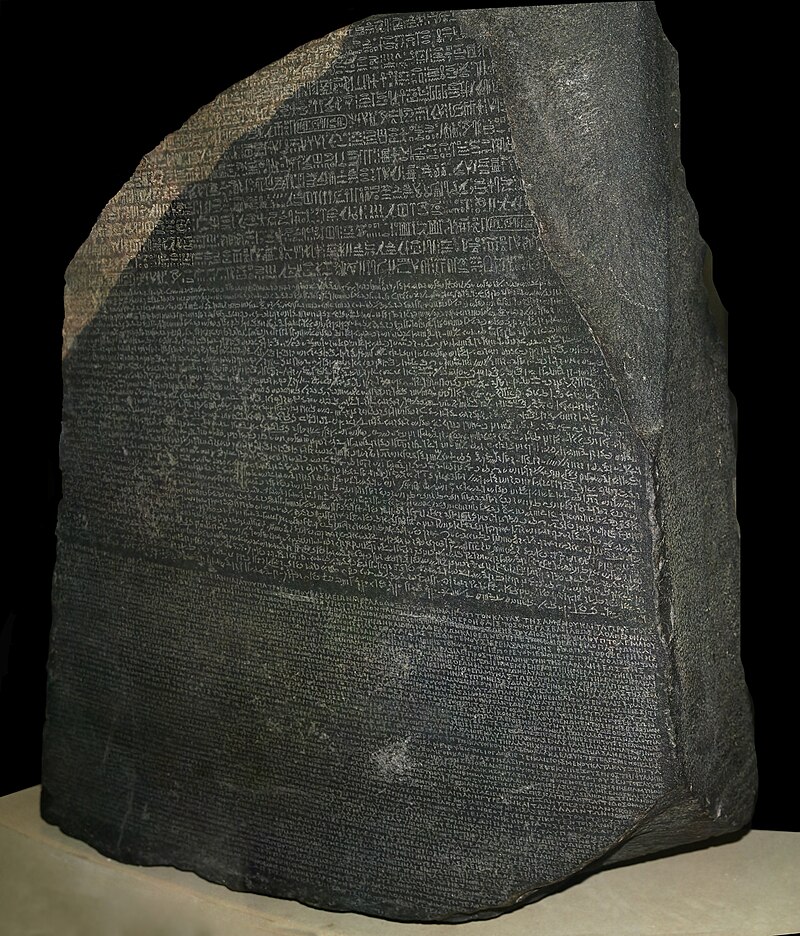

The Rosetta Stone is a large, irregularly shaped slab that measures approximately 3.5 feet tall and over 2 feet wide. It features an inscription in three different languages: ancient Greek, Demotic script, and ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Since scholars were familiar with ancient Greek, they were able to decipher the meaning and usage of the hieroglyphic symbols. Today, the stone is on display at the British Museum in London.