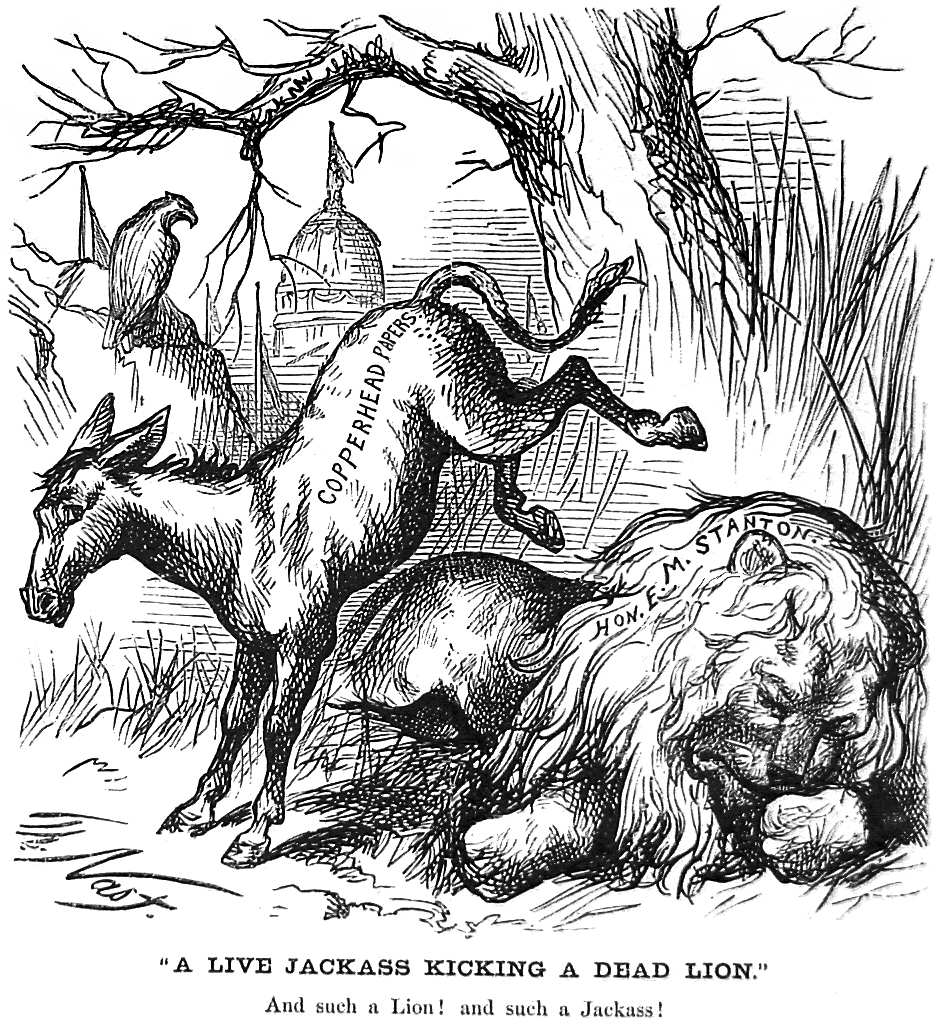

On January 15, 1870, a political cartoonist transformed an unassuming farm animal into an enduring symbol of the Democratic Party. Thomas Nast first used the donkey to represent the Democrats in Harper’s Weekly. The cartoon, titled “A Live Jackass Kicking a Dead Lion,” was a sharp commentary on the political landscape of the time.

The “jackass” in question symbolized the Democratic press, which Nast accused of attacking Edwin M. Stanton, President Abraham Lincoln’s former secretary of war, even after his death. Stanton was a controversial figure, and Nast used the donkey—a stubborn, hardworking, and sometimes obstinate animal—to encapsulate his view of Democratic opposition.

The image stuck. Nast’s cartoons gained immense popularity during the Reconstruction era, shaping public opinion and cementing the donkey as a symbol of the Democratic Party.

Why the Donkey?

While the cartoon stuck, the connection between the donkey and the Democrats actually predates Nast. During Andrew Jackson’s 1828 presidential campaign, his opponents insulted him by calling him a “jackass.” Jackson embraced the label. He even used images of donkeys in his campaign materials to highlight his resilience and populist appeal.

Nast’s genius lay in reviving and embedding this association into the political culture. His cartoons didn’t just lampoon the Democrats; they added a layer of visual shorthand that made political commentary accessible to a broad audience.

Over time, the donkey grew into more than just a tool for satire. It represented Democratic values like hard work, perseverance, and standing with the common people. The Republican elephant, also popularized by Nast, emerged in the same period, creating a visual dichotomy that still defines American politics.

Today, the donkey and elephant are inseparable from their respective parties. Though initially intended as caricatures, they’ve been embraced as proud emblems by Democrats and Republicans alike. Nast’s use of the donkey on this day in 1870 wasn’t just a clever jab—it was a defining moment in political branding.