On the Thursday morning of August 28, 1845, the very first issue of Scientific American was released in New York City. Although it was just four pages long, it marked the beginning of what would become the oldest continuously published magazine in the United States. The driving force behind it was Rufus Porter, a man whose talents and contributions defied easy classification.

Who Was Rufus Porter?

- Painter. Inventor. Dance instructor. Muralist. Poet.

- A true 19th-century Renaissance man.

- Before founding Scientific American, he experimented with several publications like the New York Mechanic and the American Mechanic.

In 1845, Porter brought his latest venture back to New York and rebranded it. Thus was born Scientific American, headquartered at 11 Spruce Street, although it was also published in Boston and Philadelphia.

What Did the First Issue Entail?

Porter promised more than just science news. His magazine would offer:

- Original engravings illustrating inventions and scientific principles.

- Essays on mechanics, chemistry, and architecture.

- Listings of American patents.

- News on innovations, both domestic and foreign.

- Music, poetry, and curious experiments.

It was part catalog, part newspaper, part scientific journal. And it was precisely what a growing industrial nation needed.

Ironically, Porter didn’t stick around long.

Within a year, he sold the magazine to Alfred Ely Beach. Why? He had other passions to pursue—particularly invention. And what a wild ride he had.

Porter the Inventor

He set up shop at The Sun Building on Fulton Street and rolled out invention after invention:

- A wind-powered gristmill.

- An early washing machine.

- A cheese press.

- A life preserver.

- A rotary engine.

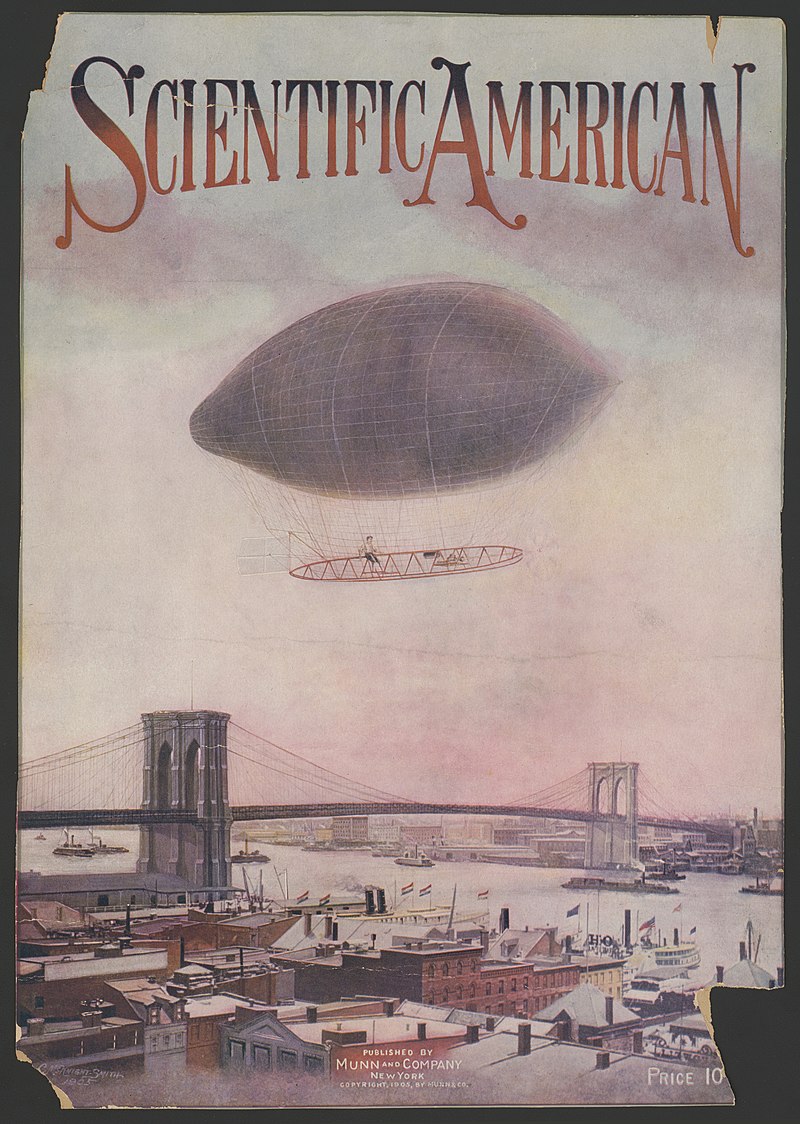

- Even an airship.

Yes—an airship.

His plan? Fly gold miners from New York to California in just three days. Tickets cost $200. Test models worked, but the full-size dirigible never got off the ground. A tornado destroyed his first hangar. A visitor accidentally tore open the hydrogen bag. His next attempt was plagued with malfunctions. Investors bailed. The dream died.

The Legacy Continues

Alfred Ely Beach, Porter’s successor, had his own dreams. He later built the Beach Pneumatic Transit—the first attempt at an underground train in New York. It ran beneath Broadway and was powered by air. Though short-lived, it was revolutionary.

Beach used Scientific American to promote his inventions and rally public support.

Scientific American has come a long way from its humble beginnings as a four-page publication. It now reaches nearly half a million readers worldwide. Topics have expanded, but the spirit remains the same: a devotion to progress, invention, and curiosity.

From murals to airships, from patent listings to planetary science, this magazine has never stopped evolving. All because one man believed knowledge should be shared, not hoarded. And it all started on August 28, 1845.