On August 23, 1856, a groundbreaking scientific discovery was presented to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Albany, New York—one that was decades ahead of its time. Eunice Newton Foote’s paper, titled “Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun’s Rays,” provided the first documented explanation of what is now known as the greenhouse effect, three years prior to the widely recognized work of John Tyndall.

A Pioneer’s Experiment

Eunice Foote, a scientist, inventor, and women’s rights advocate from Seneca Falls, New York, conducted her experiments using remarkably simple equipment. She filled 30-inch cylindrical jars with different gases—moist air, dry air, carbon dioxide, oxygen, and hydrogen—each containing a thermometer. Placing these containers in sunlight, she carefully measured how each gas absorbed and retained heat.

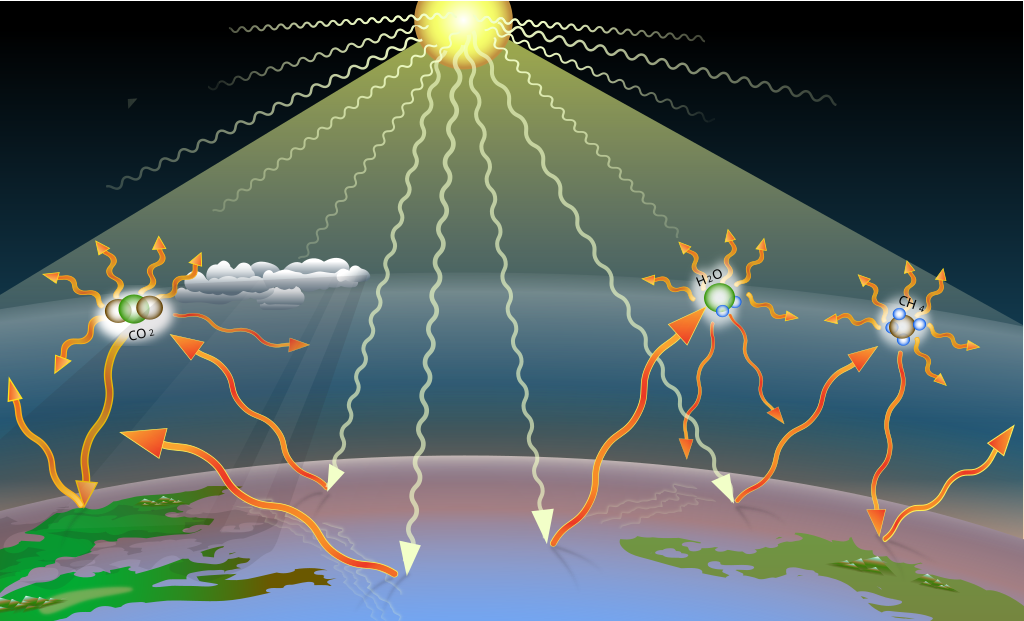

Her results were striking: the cylinder containing carbon dioxide warmed the most and maintained its elevated temperature for a long time after being removed from the sun. From this observation, Foote drew a conclusion that would prove prophetic: “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature.” She had identified the fundamental mechanism behind global warming.

The Challenge of Being Heard

Foote faced the barriers of her era. As a woman and amateur scientist in the 1850s, she was unable to present her research. Instead, Joseph Henry, director of the Smithsonian Institution and a family friend, read her paper to the AAAS assembly. Even Henry admitted difficulty in “interpreting their significance,” highlighting how ahead of its time Foote’s work truly was.

The scientific community’s reception was polite but dismissive. Scientific American acknowledged “the ability of women to investigate any subject with originality and precision,” yet the broader implications of her discovery went unrecognized. Her work was published in the American Journal of Science and Arts, but it quickly faded into obscurity.

Lost in History

Three years later, Irish physicist John Tyndall published his research on the heat-absorbing properties of carbon dioxide. Tyndall’s experiments were more sophisticated, utilizing spectrophotometry to measure the absorption of infrared radiation, a technical advancement that enhanced the accuracy of his work. As a respected member of European scientific circles, Tyndall received widespread recognition and became known as the father of climate science.

Whether Tyndall knew of Foote’s work remains debated among historians. While there’s no direct evidence that he read her paper, he was on the editorial board of a journal that republished her husband’s work, which appeared alongside hers. Regardless, Tyndall’s more prominent position and advanced methodology significantly overshadowed Foote’s revolutionary insights.

Rediscovery and Finally Recognition

Foote’s contributions remained forgotten until 2011, when a retired petroleum geologist, Ray Sorenson, rediscovered her work while collecting historical science books. This sparked renewed interest in her achievements, leading to retrospective recognition of her pivotal role in the field of climate science. Notably, historian Elizabeth Wagner Reed had recognized Foote’s importance much earlier, writing in 1992 that Foote “demonstrated what we call the greenhouse effect today.” Reed herself faced similar challenges as a female scientist, working in her husband’s shadow despite making significant contributions to genetics research.

Today, Eunice Foote is finally receiving her due recognition as the first scientist to establish a connection between atmospheric carbon dioxide and global warming. This discovery would prove increasingly relevant as humanity grapples with climate change in the 21st century.