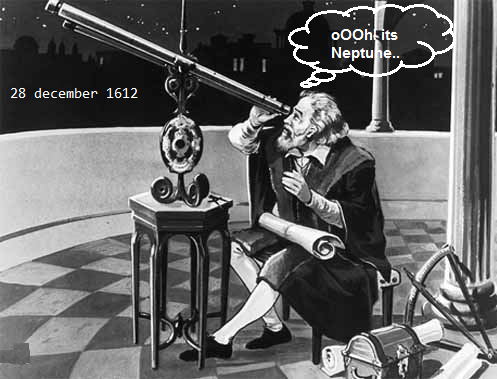

On December 28, 1612, Galileo Galilei, while sketching the moons of Jupiter, drew in his notebook what he believed to be a “fixed star” that he had observed through his primitive telescope near Jupiter. However, due to its distance from the sun and slow relative movement, he didn’t realize that what he had seen was, in fact, a previously undiscovered planet, later to be known as Neptune.

Still, it wasn’t until 233 years, in 1846, later that Johann Gottfried Galle, using calculations provided by Urbain Le Verrier and Couch Adams, officially discovered Neptune. Many other astronomers in the intervening years also observed the planet but, with its period of revolution of 165 years and faint magnitude in the night sky, it was challenging with the telescopes available to confirm its planetary status.

Although astronomers have known for decades of Galileo’s observation, they believed that he had not known what he had observed. That is until 2009 when University of Melbourne physicist David Jamieson announced a new theory. While studying Galileo’s notebooks, he realized that the great astronomer had known what he had found.

A month after his initial sighting, on January 28, 1613, Galileo observed the “fixed star” again and noted its movement, verifying that it was a planet. Jamieson theorized that Galileo had announced his discovery in an anagram and that the Catholic Church, fearing heresy, had suppressed it.

Interestingly, between Galileo’s two observations, a rare planetary event took place. Had he taken out his telescope just before dawn on January 4, 1613, he would have observed Neptune emerging from behind Jupiter.